80 years have passed since the end of World War II, but despite the march of time, that tumultuous, momentous period in our history, which saw nearly one million Australians enlist and 40,000 die, still haunts us and remains deeply personal for many Wesley families.

Wesley great grandfathers, grandfathers, fathers, uncles and brothers served in the war, and while the spectrum of their experience can never be fully absorbed, Fellow of the College and former Vice President of the College Council Philip Powell (OW1973) has spent the last three years researching and writing a comprehensive account of the war experience of the more than 1800 OWs who served. His research provides a fascinating overview of the tragedies and triumphs, sacrifices and successes of OWs at war.

‘OWs were everywhere,’ says Philip. ‘In nearly every action involving the Australian army or air force or navy… invariably an OW was there.'

The greatest numbers of OWs served in the army and saw action across the major theatres of war. We had four serving army generals: George Vasey (OW1907), Edward Milford (OW1908), John Whitelaw (OW1909) and Herbert Lloyd (OW1898). Notably, as Commander of the 7th Division in Borneo, it was Milford who accepted the Japanese surrender in that area in September 1945.

While OW involvement in the more august events is well recorded, the research also uncovers a healthy number of stories about Wesley larrikins.

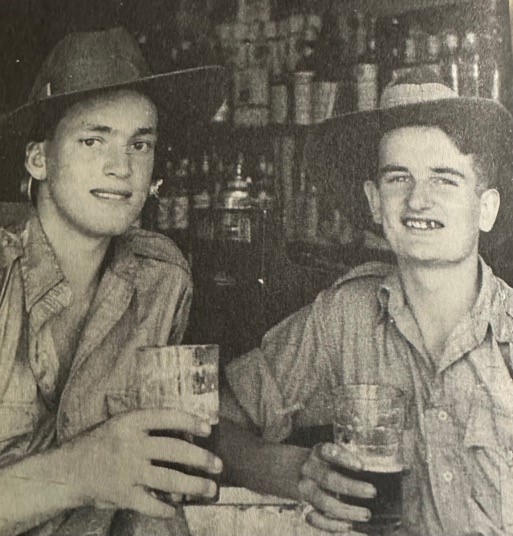

Take, for example, the exploits of Charlie Jager (OW1930) and Ben Travers (OW1936) (pictured left) who were captured by the Germans during the Battle of Crete in May 1941. They escaped into the mountains and lived with the locals for some time, before Jager was recaptured and interrogated by the Gestapo. He promptly escaped again, and they both fled by boat to Greece, where they purloined a sailboat and sailed to Egypt, getting shot at by both the German and the British air forces on the way!

The navy was the first into action in 1939, and those OWs that joined saw action around the world. Later in the war, nearly all of the young lads who left Wesley went to the navy. ‘Joining the navy was the quickest way to see action,’ says Philip. ‘You’d go down to Cerberus, have three or four weeks of training, then you’d be on a boat.’

Philip’s research also uncovered the contributions of the women who joined the war effort: MLC Elsternwick, now Wesley’s Elsternwick Campus, saw at least 19 former students serve, mainly in the army, from 1942 when Japan entered the war.

152 OWs died in World War II. Although less than a third of our OWs served in the air force, they made up more than half of our total wartime casualties. The urgent need for pilots, navigators, wireless operators and maintenance crews called for young, intelligent men who had excelled at school. Tragically, the rigours of training proved deadly for many, with mechanical failures and crashes claiming the lives of at least 18 OWs before they even saw combat. At war, we lost several fighter pilots and coastal patrol flyers, but the attrition rates in Bomber Command were infamously high, and 34 OWs lost their lives flying bomber missions.

Legendary Wesley teacher Jack Kroger was famous amongst the Wesley boys of the late 1940s and 50s for his WWII exploits, notably an adventurous escape from the Germans on a railway train that was moving PoWs from Italy into Germany after the Italian surrender in 1943. Escaping to Switzerland, Captain Kroger made his way back to Australia in 1944, was promoted to Major, and went on to serve in the Borneo campaign.

Interestingly, we also had an OW who served on the other side. Werner Wildermuth (OW1936) came from Germany to Wesley in 1935 and was in Jack Kroger’s class. A strong athlete, he won the 880 yards for Wesley at the APS sports in 1935, then played football and matriculated in 1936 before returning to Germany to start an engineering degree in 1937. In 1939, he was conscripted into the German army and, with the nickname of ‘Aussie’, served in France, Russia, Greece and Italy.

He contrived to be captured by the allies in Italy in 1944 and was sent to Egypt. Having by now rejoined his division in North Africa, Jack Kroger met his old student at the PoW camp where he was being held. Fondly recalling their reunion, Jack recounted, ‘Never has a British officer and a German soldier danced such a happy jig when they met one another.’

Philip’s book, tentatively called Come on Wesley, should be published later this year, fittingly coinciding with the 80th anniversary of the end of the war in the Pacific.