This article has been republished with permission from the author Kathy Evans, and originally appeared in the Qantaslink Spirit magazine.

In his purple pinstriped blazer embellished with a golden lion, Torey Brooking looks every inch the prefect of a prestigious private school. But home for the 17-year old student is not in a leafy Melbourne suburb; it’s in a remote town thousands of kilometres away, where ancient boab trees are rooted in red dust and the nights are lit by stars, not streetlights. “I miss it,” he says. “You’re freer on country. More alive.”

Torey is one of 60 Aboriginal students enrolled in the Yiramalay/Wesley Studio School, a groundbreaking joint venture between the Bunuba community, in the Kimberley region of Western Australia, and Melbourne’s Wesley College.

Established in 2010, its objective is to bridge the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students and, in doing so, create a community in which the First Australians, and other nationalities who call this island continent home, can forge friendships, learn from one another and develop a deeper understanding of one another’s cultures.

Wesley principal Dr Helen Drennen is a petite woman with a steely resolve that proved invaluable in overcoming the hurdles of setting up a school spanning different states, curriculums and time zones.

“This is not a project of doing good,” she says firmly. “Do-gooders in Aboriginal life are prolific and there are monuments to failure everywhere across the top of Australia. This is genuinely mutual. We have as much to learn from them as they have from us.”

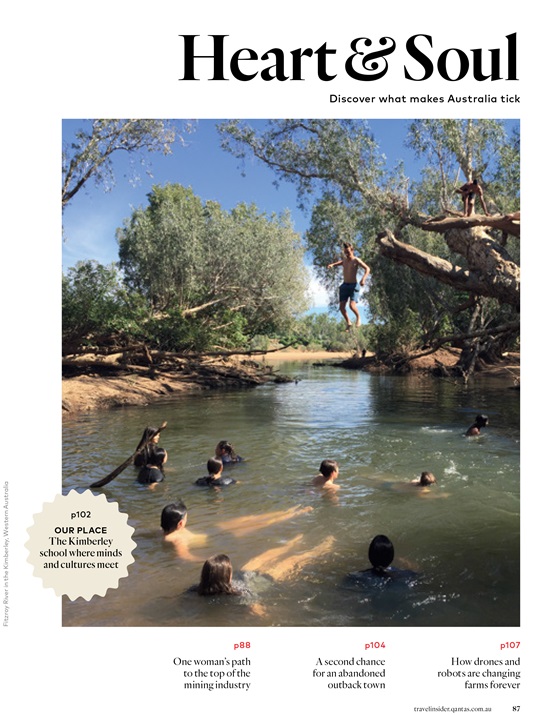

This is how it works: in Year 10, up to 20 students from Wesley go bush for three weeks at the school’s remote campus, on a cattle station 80 kilometres north-west of Fitzroy Crossing, for an Induction Program. Here they join the school’s Indigenous students, gaining cultural insights through activities such as mustering cattle, exploring art and music and making bush tucker – including learning how to catch and cook goannas.

“The local students definitely have the upper hand,” chuckles the project’s executive director, Ned McCord, a former cattleman who wears an Akubra with his suit. “They often have low self-esteem but suddenly they’re top of the class.”

When the rains come and the heat is searing, the school packs up and relocates to Melbourne, bringing with it up to 20 Indigenous boarders – many of whom, like Torey, are leaving home for the first time.

These students – whose selection is based on their commitment to education rather than their academic ability – spend years 10 to 12 moving between Melbourne and the Kimberley. During terms one and four they’re boarders, experiencing city life and mainstream schooling in Victoria; in terms two and three they return to the Studio School in their community.

Drennen believes a school that follows the seasons like this is a better alternative than offering scholarships that can wrench people from their roots. When he’s homesick, Torey knows he’ll be back on country once the rains stop and the temperature falls.

He wants to return home permanently after completing a degree in software engineering and hopes to learn how to design a computer game that may help his community address some of the lifestyle and social issues it faces.

When Drennen first visited the Kimberley in 2004, she was shocked to discover that only a small number of students had graduated from the local school since it first opened in the Fitzroy Valley in the early 1950s.

Today, the Yiramalay/Wesley Studio School – which was launched in 2010 and relies on state and federal funding as well as fervent goodwill – has an excellent attendance and completion record. The first students graduated in 2012 and, in 2016, 11 students finished Year 12 – a 70 per cent completion rate compared with the national Indigenous rate of 61.5 per cent.

This year, the school is hoping for its first university admissions. Just as important are the measurable improvements in student health, including a reduction in smoking and improved self confidence in Indigenous students as well as greater understanding, acceptance and respect for Australia’s First Peoples among Wesley students.

Sitting next to Torey in the purpose built living quarters at Wesley’s Glen Waverley campus (a far cry from the traditional images of boarding school) are Melbourne students Lachlan Girvan and Sarah Matthews, who have recently completed the Year 10 induction program.

“It was the best three weeks of my life,” says Sarah. “It completely changes your perspective. I realise now how much I took education for granted.”

Lachlan agrees: “The friendships were the best part. It was hard to leave one another.” He and Sarah use Facebook to keep in touch with the Yiramalay students they befriended. “The experience made me more mindful of how we see Indigenous people,” says Lachlan. “I don’t see [it] as ‘them and us’ any more. We have so many things in common. We’re connected in more ways than we know.”